On the Issue of Love

Materialists asks: does love conquer all? Or does money? Spoiler-free ponderings on love, dating and money

I don’t know how I feel about Materialists. No spoilers, but I went in expecting it to heal some broken part of myself, but instead, I was left cold.

Materialists is the story of Lucy Mason (Dakota Johnson, dressed like the manager-in-training at an Aritzia in Chelsea), a matchmaker for the wealthy who spends her days quantifying human characteristics into neat little boxes in order to find matches for her picky clients. She meets Harry (a dreamy Pedro Pascal, interestingly blank here) and is torn between the life of luxury she craves and the life she knows, i.e., struggling alongside her starving artist ex, John (Chris Evans, looking different but handsome as ever).

The marketing for this movie is operating on three levels:

Pedro Pascal and Dakota Johnson queening out while Chris Evans smiles along

Celine Song giving interviews about how love is the most special, powerful force ever, how it moves us, animates us and fascinates her

The tension between the romcom and the practical realities of dating in 2025

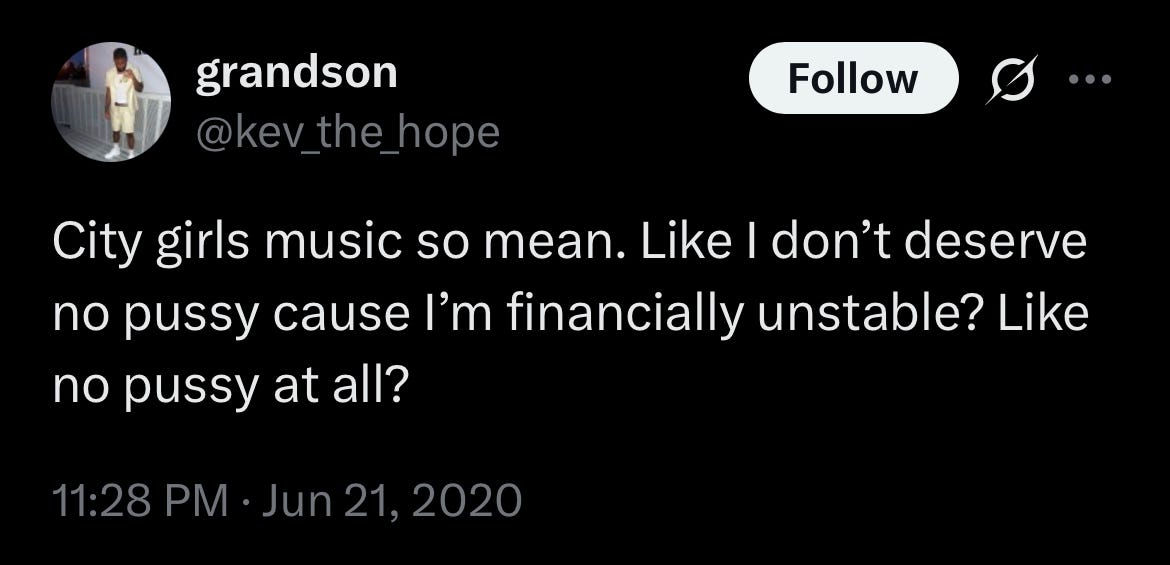

You can see why this third bullet would appeal to me: I’ve written at length about the incel-ification of the internet. Many of the themes the movie addresses have been bubbling up online for years. In fact, the only truly funny scene in the film is a montage of the insane dating requests Lucy must contend with, echoing Grindr profiles or TikTok comment sections: “no fats, no brokies, no baldies, must have the right amount of schooling, education, and breeding, can’t be too old or too young, must inspire envy among the monitoring spirits on social media”, etc.

To Celine Song, the requests are played for laughs. For those of us who spend time online, they’re a grim reality. Shera Seven, a TikTok dating coach, became immensely popular due to her frank assessment of the qualities that make people desirable partners. Overweight? Lower your standards. Single mother? Lower your standards. Only the most beautiful deserve a rich man. Men are simply means to an end: the only acceptable goal is marriage to the richest man you can attain with your given appearance and education. May the odds be ever in your favor.

Another dating coach, Kevin Samuels, preached the same ruthlessly pragmatic approach to finding a life partner, instead tailoring his advice for the red pill crowd. People would call into his live streams and he would ask them about their height, weight, income, and sexual history, and then tell them what they were capable of “pulling” and what they deserved. Samuels passed away in 2022, but not before popularizing the “high value man” concept that has since terrorized dating in the Black community.

Similar approaches to dating have become popular memes: I see them all the time on Instagram. If you’re under 6 feet tall, don’t even bother, get a measuring tape and make men prove how tall they are, “today is 5/11- or as men on Tinder call it, 6 ft”, etc. When Tinder announced its plan to introduce a height filter, men online went nuts, saying they should also introduce a weight filter or a way to see a woman without makeup: it was endless and crass.

As I’ve said before: the idea that you only deserve love if you’re the thinnest, most beautiful, most successful, most in shape, tallest person in the world is frankly insulting and odd! We live in the real world. There’s just simply no way to contort yourself to fit the myriad requirements it takes to be a “quality match”, in the words of Lucy Mason, but we’re not using matchmaking services that cost $10,000 to get in the door. Lucy spends a lot of time throughout the movie discussing math: “it just doesn’t add up, I’m doing the math, your value in the marketplace” etc. She speaks like a butcher weighing steaks or a stockbroker valuing assets. One is only worth as much as they are deemed to be worth by others.

Famously, marriage is an economic proposition. Jane Austen and Little Women both told us so. It’s easy to think of other media about dating in New York and the various economic realities therein: Friends had a “friends with money” episode which saw the group split in half due to finances and splitting a meal at a restaurant. Will and Grace trafficked in the norms of white upper-middle class New Yorkers, and Harlem had two characters on such opposite ends of the financial spectrum that their friendship and romantic foibles were played for laughs.

Lucy explains how she makes a match early on in the film: “Similar upbringings, similar levels of education, similar family structures, similar incomes…” The tidy logic of the bourgeoisie replicating itself generation after generation is a sociological fact (in The Sociology of Begging Someone to Marry You I linked to several academic sources about the highest predictor for marriage being socioeconomic status, with the upper class self-selecting itself out of the dating pool). Shera Seven and other “femininity coaches” are training young women online to believe that if they’re pretty enough, they’ll marry a Rockefeller, but the data simply doesn’t support that.

The film’s chilly romantic rationale harkens back to early Charlotte speeches from Sex and the City. Often teased as the “Park Avenue Pollyanna”, Charlotte spent the first half of the series dating intentionally: she knew exactly what she wanted. We heard her tally up the qualities of her suitors and toss away men who would never fulfill her in the way she wished, and her entire arc was about abandoning her rigid expectations in order to find the love she wished for all along.

Is marriage an economic proposition? Or is dating? Celine Song appears to be of two minds about it:

By day, she’d meet with single women rattling off requirements for a potential mate, from appearance and height to income. By night, over beers with her artist friends, she couldn’t help but notice a disconnect: Many of her favorite people would be instantly rejected based on those criteria.

“I’d be like, ‘You guys would be not good mates for any of my clients,’” she said. “I spent all day listening to these women describe them as worthless people they do not want to meet, even though I ascribe so much worth to them because they are creative and brilliant and amazing.”

In Past Lives, Nora is married to an unsuccessful writer. In Materialists, Lucy spent five years with an unsuccessful actor. Before their respective big breaks, I would bet a decent amount of money that Song and her husband, Justin Kuritzkes (of Challengers and Queer), spent a bit of time living the life Lucy fled and Nora embraced: the details of the apartments on the Lower East Side and wherever John lived (Astoria? A no man's land if ever there was one…) were astonishingly realistic, cluttered and lived-in in a way that didn’t call attention to itself.

Unfortunately, I am a hater. In an interview with the New York Times, Song says:

“When I talk to people who are really, really smart, who seem to know everything, if you start asking them about their romantic life, everything falls apart,” she said. “They’ll just admit that they don’t know things about love, or they’ll be like, ‘I don’t know, she makes me feel like a kid.’ They’ll say things that are not becoming of the put-together, intelligent people they are, because love is a mystery.”

I appreciate her frankness in discussing the mysteries of love: we live in a society where romantic partnership is prized, venerated, and exalted, but to admit you want a partner is seen as deeply embarrassing. We’re meant to glide into partnerships effortlessly.

Song has spent the press tour talking about how love is a unique, life-changing force, but when you’re on the outside, love is opaque. It’s not lost on me that I’m exactly the person she’s talking about above, but dating is one of the most discussed topics on the internet today: there are endless terabytes of content, videos, advice columns, podcasts, books, seminars, gurus, and coaches all promising to help you find the love of your life.

Despite this, there is no science to meeting someone and making them your “person”. It doesn’t surprise me that people are looking for cheat codes to explain to them something that feels so inexplicable. I do not agree with the language of evaluating yourself like a piece of meat (a Dasha jumpscare during the film evaluates the pain of being an average woman: it’s impossible to stand out if you don’t have any special characteristics in the market, but if you don’t fit into a “niche” you’re relegated to limbo) but I understand the impulse to make sense of a force that feels beyond sense-making.

Trying to explain what it feels like to be single today to someone in a relationship feels like that one Carrie Bradshaw meme: you just don’t get it. I don’t agree with people listing their characteristics like real estate agents trying to make a sale, but in my most empathetic heart, I understand why people would seek simple explanations for the inexplicable. It’s easier to try to quantify a harsh reality, mapping context onto ephemera, than it is to do the hard work of healing whatever else is going on. It’s easier for a man to blame his height, his income, his hairline, and his body than it is to plumb the depths of the true darkness that could be keeping him alone.

Does love conquer all? Or does money? Materialists gives us an answer (I won’t spoil it) but I don’t trust it. It’s not a romantic comedy— it’s neither romantic nor funny, which is simplistic but must be stated plainly. In the end, the only thing I felt at the end of the movie was cold.

The film makes a point to distinguish between love and dating: love is easy, dating is hard. The rest? You know what I’m going to say: the rest is math.

I love talking about this stuff, truly. Materialists would have been right up my alley if it was more about matchmaking. I could’ve spent hours listening to those insane people list the qualities that make up their dream partners.

Also, one of my favorite lines in the movie involves the self-mythology of “big, happy families”. In Jennifer Close’s The Hopefuls, she talks about how big families are in love with their own mythology and are always aspiring towards Kennedy iconography. “All it takes to be a big, happy family is to believe you come from a big, happy family.” Drag them!

It’s fascinating that Past Lives was so perfect— almost tangible in its longing, epic in its yearning, beautiful and devastating— and this didn’t work for me. I’m trying not to read too much into Song’s life but the Past Lives/Challengers/Queer/Materalists canon is giving me some fascinating thinking material.

Art (Challengers), Arthur (Past Lives), and Harry (Materialists) all sleep in the same position: supine and almost feminine in their positioning. It stuck out to me because a friend told me she would have left Arthur immediately for seeing him sleep like that, and another friend physically recoiled when they showed Pedro Pascal in bed. Not sure what it means but it’s fascinating!

That said, Zoe Winters is absolutely incredible. There’s a plotline that will make a lot of people pause, but she demolishes the material and is high-key the best part of the movie.

I had so many feeling about this movie I banged this out in a few hours. I’m trying to find the right balance between research paper and tweet for these while also not falling into the more, better, faster trap.

Another Materialists review: cc: Helmet Girl HATED it. I’m excited to see more people talk about the movie, I’m going to go post my review on TikTok now.

While I did like this movie, it was definitely not as effecting to me compared to Past Lives which remains my fav.

I’m not much of a romance consumer in books or movies, so Celine incorporating the dialogue and harsh truths that I do think a lot of romance films miss I loved because while talking about money, rent, not affording the life you want etc often kills romance I found it refreshing to say that part many people navigate refreshing. Also love a New York setting.

But I do agree, now that I think more on it, it didn’t warm my heart as I would’ve liked and I do think this movie is marketed wrong. It’s NOT a romantic comedy at all. There’s funny scenes but it’s a drama (which I also don’t mind but I think it sets up a wrong expectation). Lastly, I heard a critic about Dakota as an actress being the leading lady and how she doesn’t have the range to lead a movie emotionally and I do think I kind of agree. She is a bit emotionally rigid and I think it left her character feeling not as dynamic which I think contributed to the cold feeling. I want to watch it again but I overall did like it! I also loved how it was shot.

Let’s be honest, take out a few details and I can recommend 20 Hallmark movies with this exact plot.