The Pretty Problem

TikTok's obsession with beauty is seeping into everything

In March, an influencer decided she wanted to be more beautiful, or “glow up”, in TikTok-speak. She went on Pinterest and found 100 of the most beautiful girls on the app, and then classified their features in order to emulate them (and gain more followers, natch). 83% of the girls had lip filler. 81% had fluffy brows. 86% had solid colored hair, 89% tanned, and 95% wore light makeup in their pictures. She cracked the code, got some hair extensions, and watched her followers climb.

While this story has all the features of a YA dystopia, hundreds of people log onto the app everyday to beg strangers on the internet to list all the features they can “fix” in order to become more beautiful. Gen Z has gamified beauty. If you’re more beautiful, you can get followers, which leads to money, which leads to happiness. Millions of people believe they can inoculate themselves from ever feeling any pain if they’re the youngest, the thinnest, the most beautiful, and the most rich.

It makes sense, to a degree. TikTok’s algorithm is notoriously selective. People who are white, young, tan, thin, and beautiful explode onto the scene because the algorithm likes their look. Charli D’Amelio and Addison Rae, two people who combine the excitement of smiling with the thrill of just standing there, became household names because their faces were symmetrical while they shuffled around their bedrooms. This week I learned that even lighting matters: the algorithm is rumored to deprioritize people who have warm overhead lighting, in what the kids are calling “poor people light”.

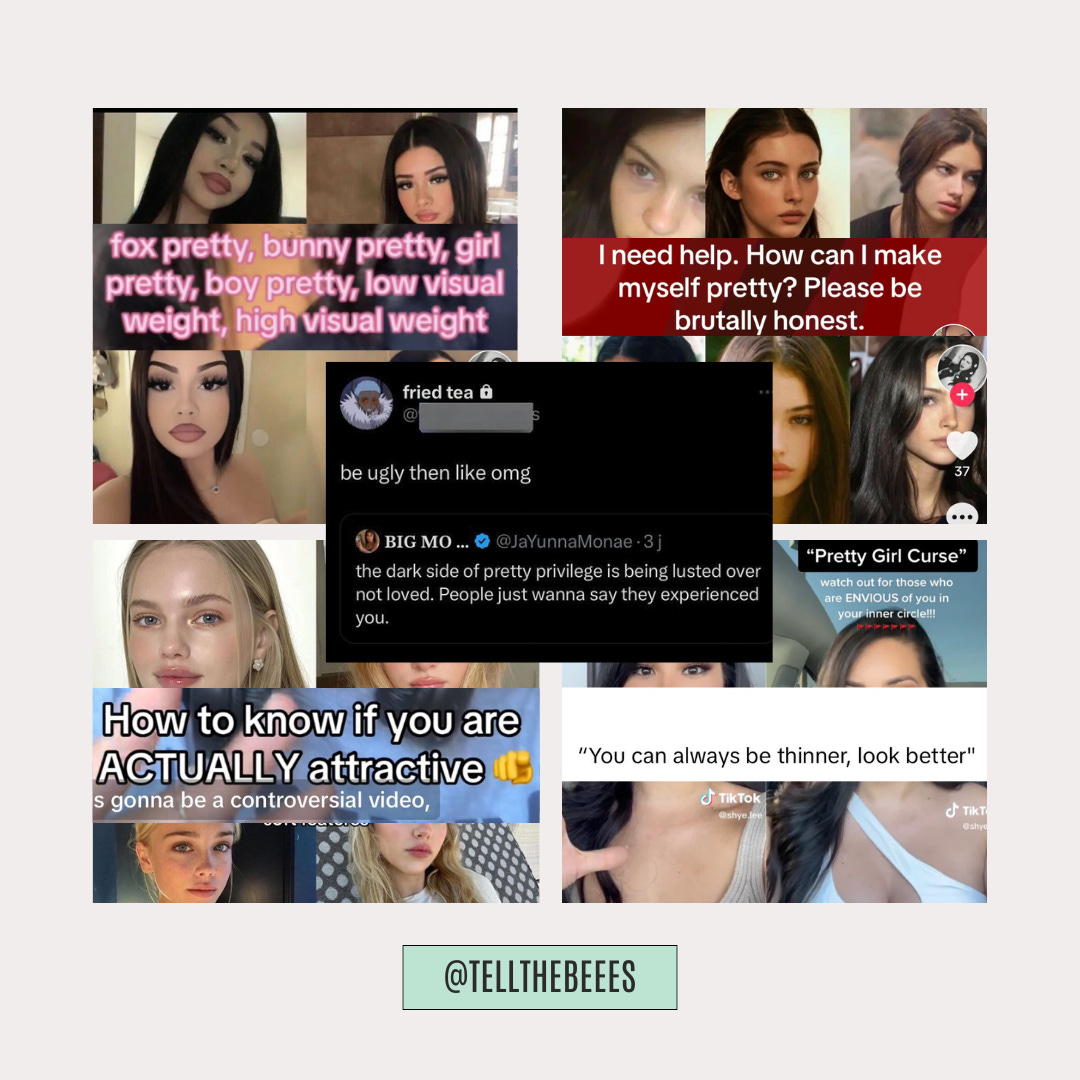

I see the captions everyday: I spent hundreds on an eyebrow serum that made me look old. What can I do to make myself prettier? How do I find out my visual weight? Why is there an ugly person on my television? What are the downsides of pretty privilege? You could write a (very sad) book with the captions floating around TikTok. Something has gone very wrong with the generation that was supposed to free us from draconian beauty standards, and every day we drift further towards a future that further reifies multiple distinct forms of oppression.

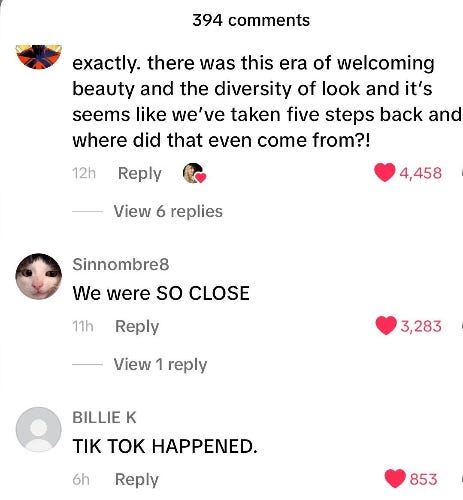

I don’t mean to specifically pile on Gen Z, although they know this is an issue too (see the image above). For years scientists have published papers about Instagram warping the minds of teenagers. I’m sure in a few years we’ll see studies about TikTok doing the same. The starkness of the shift is what surprises me. Millennials grew up with the tyranny of 90s beauty standards before the body positivity movement (which isn’t perfect, of course, but it was something!) allowed different body types and diversity to permeate runways, editorial shoots, television shows, and social media. In the past few years, there’s been a stark shift in what’s permissible, what’s allowed, what’s accepted, and what’s celebrated.

It’s easy to see why beauty would capture the imaginations of people online. Beauty is salient, there are visible external rewards for achieving it, for mastering the tips and tricks and elements that give one elevated social currency. There are rewards for it outside of social media, of course, but how many of us have stumbled upon a video of an attractive young person listlessly lipsyncing to a song and wondered why it went viral? Instagram may have pioneered the look that dominated the 2010s, but TikTok has gone a step further in codifying and classifying who exactly is deserving of the benefits.

Fox pretty, bunny pretty, doe pretty, boy pretty, girl pretty, natural pretty, TikTok pretty, high visual weight, low visual weight, positive canthal tilt, neutral tilt, negative tilt. In the past two years, dozens of terms have flooded the app, forcing people to separate themselves into groups with ambiguously ascribed social value. Boy pretty and girl pretty rankle the most: it’s middle school all over again, determining your worth based on whether someone wants to hook up with you. Again, I understand that these people are young, but it’s worrisome that this logic is infecting an app with so many young people on it. Not everyone is going to want to hook up with you, and not everyone should!

The most horrifying aspect of all of this is the slow slide into eugenicist logic: the canthal tilt trend raised eyebrows, but once I investigated more it became clear that many people were simply spouting race science. Sociologically, I have to say I saw it coming: when one group decides that beauty is a dichotomy, split into “good” and “bad” (pretty vs. ugly), then of course the denigration of the lesser group must follow. It’s fascist logic made manifest. We’ve seen it all before, and the snowballing of (pretty obvious) racism is one trend we should all keep an eye on and work to combat.

The obsession with beauty trickles into other spaces. When the cast of Mean Girls (2024) was announced, hundreds rushed to TikTok to discuss how ugly they found the cast. In 2022, I made several posts about the odd way people talked about Pauline Chalamet’s character on The Sex Lives of College Girls, and how she didn’t “deserve” to hook up with attractive men. Someone recently questioned how Hannah Horvath on Girls pulled all the men she did (with the unspoken assertion that she is too ugly to have hot boyfriends).

It is not lost on me that when a form of media displays a woman deemed unattractive by society living her truth or being a whole, fully formed character with drive and ambition (outside of her appearance), said media receives societal pushback. Lena Dunham was ruthlessly criticized when One Man’s Trash aired way back in 2013, right before body positivity took hold in a real way.

In a way, we’re always having the same circular conversation, instead of the one we should be having: who decides? Why are we internalizing rules about who is worthy and who isn’t based on these standards very few of us can ever hope to reach? Imagine waking up every day and deciding whether you’re allowed to go outside, or speak publicly, or work, or fall in love based on the whims of 16 year olds with iPhones. A tribunal of surly, insecure children being the arbiters of whether I’m allowed to exist as a person? I’d rather go back to middle school.

There’s truly so much more to say, but I already went long. The “down sides of pretty privilege” conversation is just people discovering standard grade misogyny.

I couldn’t begin to plumb the depths of fatphobia and ableism tied up in all of these conversations on top of looksmaxxing and incel logic. It’s a cluster!

If you want a more scientific look at beauty and plastic surgery trends in the UK, Face Value had a great write-up here.

Dazed Digital wrote about the rise of TikTok face and “algorithmic sameness”.

TtB Book Club: Our online meeting is on Sunday at 11:30 ET! July’s book post will go up Monday, and I’m aiming for a meeting date of 7/31 IRL, 7/28 online.

Finally: I’m writing an article about queer open relationships and cheating and looking for people to speak to! (The angle is more sociology and less judgment, I promise!) If you have experienced cheating and are no longer with your partner or you have and you are, I’d love to ask a few questions about boundaries etc. Nothing salacious, I promise!

as much as the literati likes to mock and deride young women BookTokkers, I think romanticizing the cultivation of the life of the mind is so much healthier than chasing and promoting beauty trends… girl, inject your brain not your lips

It’s so depressing.. I feel like so many of the women my age are so plugged in to the online beauty standards and even the ones that aren’t still adhere to the trends, just a little later.

More women need to hear this quote: “pretty” is not the rent you pay to exist in this world as a woman.