Who Gets to be Condescending?

On the construction of celebrity, the double bind of likability, and woman-hating online

A few months ago, Woman of the Hour premiered on Netflix. The movie serves as Anna Kendrick’s directorial debut and received fairly mixed reactions from fans of the true crime genre due to its lack of salacious details and avoidance of gore. I famously don’t love true crime, but I tapped in as a Kendrick enjoyer.

Anna Kendrick stars as Cheryl Bradshaw, an actress in her thirties palpably pulsing with disappointment at her lot in life. In the opening scene of the present timeline, it’s quickly established that Cheryl has spent many, many years in the Hollywood rat race. Casting directors simply don’t know what to do with a girl like her, especially not in 1978. She’s too smart, too aware, too angry. They dismiss her and the movie begins in earnest.

Kendrick has occupied a few different positions in the Hollywood starlet pantheon. Real ones (baby queers and theater kids) were introduced to her in Camp (2003), where she played the silent, furious Fritzi, a sycophantic sidekick who channeled her rage into an iconic performance of “The Ladies Who Lunch” after poisoning her bully/crush. She played the best friend role in Twilight and New Moon with aplomb before ascending to mainstream stardom with Up in the Air, where she received an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress.

Up in the Air is fascinating because the casting department understood Kendrick on a cellular level: in the film, Kendrick plays Natalie, an ambitious, rigid go-getter who has her life mapped out at 23 years old. She has her job (she spearheads laying people off via Zoom, a novel concept in 2009), she has her boyfriend, and she has social norms she adheres to religiously. Life works out for girls like her. (It should not be a spoiler for a 15 year old movie that the character quickly receives a rude awakening.) Her next big role was in Pitch Perfect, which made her a Gen Z icon. There, she plays Beca, an acerbic wannabe producer who disdains everything but finds her joie de vivre through the power of a capella.

It’s worth noting that for many Millennials, self-deprecation, surliness, and playful meanness were common in that era. Kendrick’s Twitter blew up between 2011-2016 because of a cultural moment that celebrated “she’s so crazy!” culture (Aubrey Plaza benefited from the same thing on Parks and Rec, where her determined, put-upon hostility was a direct counterpoint to the Obama era optimism of Amy Poehler’s Leslie Knope). Her public persona was cemented: she was quirky, hot, and ~funny~. In 2014, Elle named her the “Sexiest and Savviest Social Media Star of Her Generation”1. Her Twitter bio at the time read “Pale, awkward and very very small”. (It currently reads “Kind of a lot.” She is the most Millennial to ever Millennial.)

As you can imagine, playing characters who were rigid, unpleasant, or off-putting combined with a public persona as a quirky, misunderstood weirdo did not do wonders for her public perception. I did a deep dive of my own Twitter archive and while I was consistent in my support, people outside of the Millennial cringe/theater adjacent/self-deprecating misfit mold did not vibe with her. The criticism I heard most often was that she seemed like a know-it-all, she seemed condescending, and she had “resting bitch face” (words I dread to even type as a man).

In her book, Scrappy Little Nobody, Kendrick reveals a deep and abiding insecurity that haunts her to this day. She wrote about never feeling like she fit in with anyone, about how being a working actor at age 12 isolated her from her peers, and how moving to Los Angeles instead of going to college further separated her from everyone she knew. She seems uncomfortable with most things, and uses “humor” as a defense mechanism. It’s fascinating that she wrote all of this in 2016 and doesn’t seem to have done much self-reflection: I listened to the Call Her Daddy episode she did in October to promote Woman of the Hour and all her old wounds still sting. She doesn’t have many friends: her Pitch Perfect costars beg her to hang out with them and she doesn’t answer their texts, preferring to self-isolate.

Anne Hathaway, a similarly theater adjacent but much more beloved actor, came under fire last year for a similar vibes based offense. After being spotted sitting next to Anna Wintour, the inspiration for Miranda Priestly’s character in The Devil Wears Prada, an interviewer asked her what Wintour and Hathaway discussed. Playfully, Hathaway says “Why would I tell you?” before laughing. The internet went ballistic, accusing Hathaway of being condescending, being “passive aggressive” and “having mean girl vibes”. We don’t have to cover the Anne Hathaway hate train all over again—Anne Helen Petersen over at Culture Study did it perfectly— but it’s worth noting that Hathaway’s great sin in this instance was… seeming unpleasant. The context of her words didn’t matter to the internet, all that mattered was she was a woman who “behaved badly”.

I’ve talked about the Double Bind of Likability before in the context of reality television. An anthropological term used to describe a situation where any choice made will be wrong, it’s become commonly used to discuss women in corporate positions of leadership:

“If you're too likable, you're seen as personable but not powerful. If you're too authoritative, you're seen as cold and lacking warmth. This is the double bind that women in the workforce face: You're either too soft or too tough, but rarely just right.” (Forbes.)

Some version of this was explained to millions during Barbie through America Ferrera’s speech: it is often impossible for women to do the “right thing” when every choice has a negative connotation or is seen as a misstep. Anne Hathaway spent a decade smiling nonstop and celebrating her Oscar win almost destroyed her career. Anna Kendrick spent a decade telling us she hated everything and alienated millions. It’s a tightrope few have perfected. Over the last five years, Hathaway has stepped into her power by telling us how she doesn’t care what we think of her anymore. Good for her.

For an actor of color, the double bind grows even more fraught. Rachel Zegler seems to have bargained with the wrong devil for her career: from being discovered through open auditions for West Side Story (which was delayed due to Covid), to an awkward press tour where she had to dodge questions about a costar being accused of assault, to being lambasted for saying she took a role in Shazam 2 for the money, to being crucified multiple times on the Snow White press tour, it’s clear she’s had awful luck. The first Snow White controversy occurred at a Disney event where Zegler celebrated the feminist nature of the new film:

“I just mean that it’s no longer 1937. We absolutely wrote a Snow White that ... she’s not going to be saved by the prince, and she’s not going to be dreaming about true love; she’s going to be dreaming about becoming the leader she knows she can be and that her late father told her that she could be if she was fearless, fair, brave and true.”

Fans descended upon her for allegedly dishonoring and disrespecting the legacy of the original film. It’s worth noting that this entire drama felt overwrought: no one’s favorite movie is Snow White, and I’m on the record as saying it sucks. It’s simply not that good a movie and people allowing nostalgia to cloud their feelings for a working actor is ridiculous. Disney fans and Disney Adults are notoriously hard to reason with (a collection of people who’s only emotional trigger is nostalgia and adults gleefully consuming media made for children, literally two of my least favorite types of people) but they were eager to call Zegler smug and pretentious, and saying they always knew she had “bad vibes”.

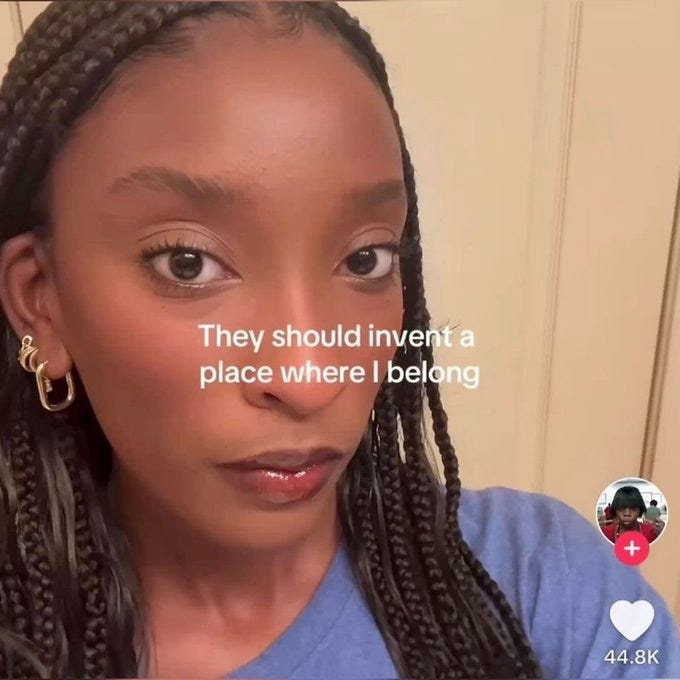

Zegler stepped in hot water again when she said she had only ever seen the original film once. Fans said she had no connection to the character and that not every woman needs to be a girlboss. Disney Tiktokers stoked the flame by calling Zegler “incredibly off-putting” and commenters said “her career was over”. Zegler’s case is interesting because she emulates the best and worst public personas of Hathaway and Kendrick: clear theater kid earnestness (her interviews about Romeo + Juliet, the way she discusses singing and performing in The Hunger Games: The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes) with refreshing “down to earth” jokes (the above comments about Snow White and press for Shazam 2).

To me, it shouldn’t be a surprise that these women are criticized: again, the double bind is present for all female actors and we live in a deeply misogynistic society. It’s interesting that the label of condescending is seemingly always thrown at intelligent women who aren’t performing gentility or sweetness.

We see this often in the Housewives universe. The Housewives franchise thrives on casting certain archetypes: brashy villains, weepy victims, mean rich women, delusional legends. Across the franchise, cast mates who serve as the intelligent “voice of reason” are often punished by fans for wielding their intelligence as a weapon. Carole Radziwill (journalist turned Kennedy widow, RHONY) was constantly attacked for her aloofness and imagined condescension, while Countess Luann was never checked for her own haughty comments (pre-arrest, of course— Luann has lived a lot of different lives).

Being one of the few places Americans can see women over 50 doing…anything, really, the Housewives franchise should be a place for women to live their truths and express themselves outside of the shackles of respectability. Instead, being on r/housewives for four years has taught me that women can be criminals, can drive their cars into houses, can lie, cheat, and steal, but the most unforgivable sin? Using big words in an argument or mentioning you went to law school.

Anti-intellectualism has been rising for years. I have a whole playlist about the different ways it manifests, and the cultural conversations around both intelligence and learning have been shifting in ways that are giving many people pause. Celebrity culture might seem trite, but it’s long been one of the ways media researchers track public sentiment around hot-button issues. Correlation doesn’t equal causation (and Hathaway and Kendrick’s management of their public personas has been a decades-long ongoing project) but this societal urge to punish women for speaking out of turn, for not being meek or docile, or for speaking up in general is somewhat concerning.

The Overton Window doesn’t tend to shift back on these things: once it’s deemed acceptable to attack a woman online, it’s usually open season on her for years. I want us to be aware that when we talk about certain women having “bad vibes” or seeming holier-than-thou, sanctimonious, or aloof, we’re operating within a pretty standard framework for ensuring women remain in boxes. Simply acknowledging the tightrope exists isn’t enough (but thank you, America Ferrera and Greta Gerwig): we’re all complicit when we side with the internet on who seems kind, or smart, or loving. Not to be all Bushwick about it, but hating women based on vibes is gauche. Celebrities are constantly telling us who they are. Celebrities are constantly messing up. If you need a reason to hate one, I promise, they’ll give you one. The only question I ask is: is this a real reason, or are they just not conforming to an imaginary ideal of how you want women to behave?

Morality Slogans

The TtB Book Club will be meeting in mid-January! Q4 was brutal. We’re reading Euphoria by Lily King.

I did a round-up of books about friendship for Open Book Club’s Substack: I shouted out a few of my faves.

I was also a guest on the Go Touch Grass podcast and discussed Ariana Grande and Ethan Slater.

I don’t really know what to do about the looming TikTok ban. I’m on Instagram, but it seems like I have to download all 600 of my posts from over the last two and a half years and upload them somewhere. YouTube terrifies me and IG reels is evil so I’m kind of stalling on this. Suggestions welcome!

I think for posterity’s sake (and because I’m always referencing myself) I will want to download everything and upload them somewhere so I can continue to share them, but the discoverability is the issue: do I want to contend with demons on Instagram or get zero views for everything on YT? A true Sophie’s Choice…

Planning my content for the end of the year/beginning of Q1: I’m doing an author interview, the year in discourse, and my favorite books of the year.

It speaks to the hollowing out of media that an article from 2014 has had its images purged from the internet. Who is paying for hosting over at Elle?

I'm here to comment on possibly the least important and least interesting thing in this whole important interesting newsletter, which is your note at the very end about the hollowing out of the media and dead images from an article in 2014.

The impermanence of online media is remarkable. I see mainstream media publications filled with link rot even in internal links, and my mind was blown when The Awl (a widely read respected publication from Choire Sicha) accidentally let their domain expire. Oops!

Sometimes I think I keep my old publications live just out of a sense of commitment to the bit, a cultural archive of how the web was, going back to 2007... but I recognize that very folks see it that way.

Ultimately, we're all responsible for archiving our stuff. I vote you put your vids on both insta AND YouTube. Shamelessly enjoy those 0 views and know that you're doing your work as a cultural archivist.

Absolutely gleeful to hear you were a podcast guest, since I listen to your TikToks wishfully like they're podcasts. If it were up to me, full-time podcasting would be your post-TikTok pivot (selfishly).